CHRONICLES OF AGINID

CHRONICLES OF AGINID

Legends and myth have been told about how the ancient name of Cebu originated and none of these versions have so far held up to the scrutiny of scho-lars and historians until Jovito Abellana published his book ‘Bisaya Patronymesis Sri Visjaya’ where he extensively covered the period in ‘Aginid, Bayok sa atong Tawarik’, which translates in English to – Glide on, Odes to our History.

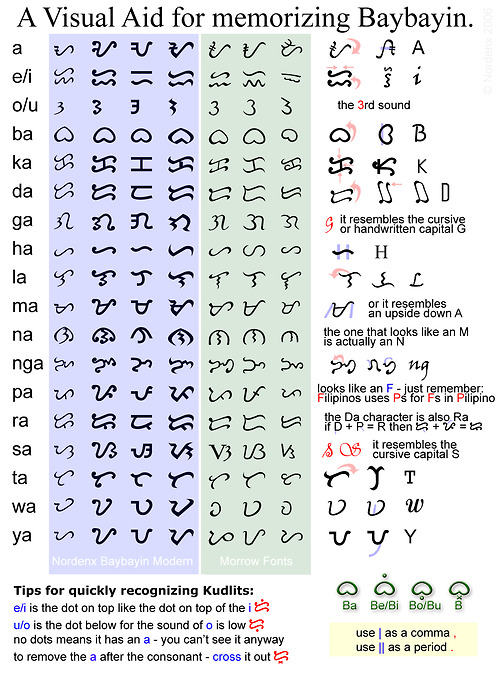

Remarkably, Abellana wrote Aginid in a Cebuano hieroglyphic form called ‘alibata’ (or Baybayin) with an English translation. The Aginid recounts a fiery story of pre-colonial Cebu then known as ‘Sugbo’ – which means, scorched earth. This version on the origins of the term ‘Sugbo’ is important because the name describes in detail historic events and establishes the basic hypothesis why eskrima, arnis and kali (a class of Filipino martial arts) were invented in defense against local invaders.

In those times Sugbo (now present-day Cebu City) was part of the island of ‘Pulua Kang Dayang’ or ‘Kangdaya’. The an-cient poem ‘Diyandi’, was written during the time of Datu Tu-pas – a chieftain of Cebu and son-in-law of Rajah Humabon, and probably after the arrival of the Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan in the Philippines in 1521 (image, right).

In those times Sugbo (now present-day Cebu City) was part of the island of ‘Pulua Kang Dayang’ or ‘Kangdaya’. The an-cient poem ‘Diyandi’, was written during the time of Datu Tu-pas – a chieftain of Cebu and son-in-law of Rajah Humabon, and probably after the arrival of the Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan in the Philippines in 1521 (image, right).

The poem instructs us that hundreds of years ago inhabitants in the central part of Cebu island burned down a town known as Sugbo as a way to drive away sea pirates. Accomplishing this deed, they would then flee to adjacent mountains but later launch a counter-offensive against the demoralized and exhausted invaders. It is a stirring chronicle of the story of the rich culture and colorful history of pre-colonial Cebu in the Philippines and reveals its links to a powerful Hindu empire.

A TURN OF MIND

A TURN OF MIND

The Chola, surname of a family who founded an an-cient Tamil dynasty in Southeastern India were one of the longest-ruling dynasties in that part of the world. During the period 1010–1200, its territories stretched from the islands of the Maldives in the south to as far north as the banks of the Godavari River in Andhra Pradesh. They annexed parts of what is now Sri Lanka and sent an expedition to North India that touched the river Ganges where they defeated the Pala ruler of Pataliputra in Mahipala. Thereafter, they success-fully invaded kingdoms of the Malay Archipelago, then occupied Sumatra and part of the island of Borneo in Indonesia installing members of their own family as rajahs (kings) to rule over the local inhabitants until the dynasty itself went into decline at the beginning of the 13th century with the rise of the Pandyas, who ultimately caused their downfall.

The Rajahnate of Cebu, a classical Philippine state which existed in the centre of the Visayas region prior to the arrival of the Spanish, was one founded by Sri Lumay or ‘Rajamuda Lumaya’, its first ruler. He was a minor but ambitious native prince from Sumatra who traced his ancestry to the Chola dynasty. It is said that he was sent to the Philippines by the ruling maharajah to “es-tablish a forward base for expeditionary forces.”

The Rajahnate of Cebu, a classical Philippine state which existed in the centre of the Visayas region prior to the arrival of the Spanish, was one founded by Sri Lumay or ‘Rajamuda Lumaya’, its first ruler. He was a minor but ambitious native prince from Sumatra who traced his ancestry to the Chola dynasty. It is said that he was sent to the Philippines by the ruling maharajah to “es-tablish a forward base for expeditionary forces.”

The Philippine archipelago was strategically positioned in Southeast Asia that it naturally became part of the trade route of the ancient world. Agricultural products were bartered for Chinese silk cloths, bells, porcelain wares, iron tools, oil lamps, and medicinal herbs. From Japan, perfume and glass utensils were usually traded for native goods. Ivory products, leather, precious and semi-precious stones and sarkara (sugar) mostly came from the Burmese and Indian traders. The Maharaja of Sumatra obviously wanted to extend his influence and protect his interests in all these lucrative trading activities but was thwarted when Rajamuda Lumaya took a turn of mind and rebelled by establishing his own independent Rajahnate instead.

A FAIR AND JUST RULER

A FAIR AND JUST RULER

Between the 13th and 16th century AD the island of Cebu (then known as Zubu) was one inhabited by Hindu, animist and Mus-lim tribal groups all ruled by Rajahs and Datus (chieftains).

In folklore of the Visayan people, Rajamuda Lumaya is said to have sired several sons and for a time established a dynasty of his own. Of these sons Sri Alho (the title ‘Sri’ is a Sanskrit word, with a primary meaning of radiance, or diffusing light and often used as a title of veneration) ruled a land known as ‘Sialo’ which included the present-day towns of Carcar and Santander in the southern part of Cebu island.

Another son, Sri Ukob, ruled a kingdom known as ‘Nahalin’ in the north which included the present-day towns of Consolación, Liloan, Compostela, Danao, Carmen and Bantayan. Sri Ukob died in battle fighting against a Muslim piratical group known as the ‘Magalos’ from the larger island of Mindanao.

The youngest of his sons was Sri Bantug who ruled a kingdom known as ‘Singhapala’, in a region which is today known as Cebu City. He died in an epidemic which spread in the island and was succeeded by his son Sri Hamabar, also known as Rajah Humabon.

Rajamuda Lumaya also had another son known as Sri Parang the Limp, He could not effectively gov-ern his kingdom because of his infirmity so he handed his throne to his nephew Humabon who became the Rajah of Cebu.

Rajamuda Lumaya also had another son known as Sri Parang the Limp, He could not effectively gov-ern his kingdom because of his infirmity so he handed his throne to his nephew Humabon who became the Rajah of Cebu.

Although a strict disciplinarian, Rajamuda Lumaya was also known to be a fair and just ruler that not a single slave ran away from him. During his reign, the Magalos (a term that literally means ‘destroyers of peace’) often invaded the island to loot and hunt for slaves. Each time these raiders appeared over the horizon, Rajamuda Lumaya would commandeer his followers to burn the whole town in order to drive the invaders away empty-handed. The Rajahnate of Cebu continued to fight on for several years against the slave traders even forming an alliance with the Rajahnate of Butuan to strengthen their efforts.

Rajamuda Lumaya was eventually killed in one of the battles against the Magalos and was succeeded by Sri Bantug. Bantug carried on his father’s rules throughout his reign. He organized ‘umalahukans’ (reporters) to urge people to obey his orders, especially on agri-cultural production, trade and defense.

AN ANTAGONIST ARISES

AN ANTAGONIST ARISES

Then a new actor enters the stage. Lapu-lapu Dimantag ar-rived from Borneo and asked Rajah Humabon (Sri Bantug’s son) for a place to settle. Being an ‘orang laut’ (man of the sea), Humabon offered the island of Opong but Lapu-lapu was convinced instead to settle in Mandawili (now Mandaue) and make that land productive much as it was virtually impossible to cultivate food crops in Opong island due to its rocky ter-rain.

Under Lapu-lapu’s leadership, the economy of the island flourished largely because of the goods he brought from the land and sea in northern Cebu that increased trading. With his power and influence now growing, it did not take long for his relationship with Humabon to sour. This happened when Lapu-lapu decided to become a ‘mangatang’ (pirate) and worsened still when he converted to Islam and swore allegiance to Sultan Kiram to gain protection for his lucrative activities.

Bolstered by an alliance that protected his flanks, Lapu-lapu ordered his men to loot ships passing through Opong Island which significantly lowered trading transactions for the Rajah of Cebu. This created tensions between Humabon and Lapu-lapu. Opong Island thus earned the ill-reputed name ‘mangatang’ which later was shortened to the word Mactan.

PORTENT OF THINGS TO COME

The phrase ‘Cata Raya Chita’, a warning in the Old Malay language given by a visiting merchant to Rajah Humabon, foretells what could befall the Rajahnate if care is not taken to avoid conflict with a new force looming over the horizon:

“Have good care, O king, what you do, for these men are those who have con-quered Calicut, Malacca, and all India the Greater. If you give them good reception and treat them well, it will be well for you, but if you treat them ill, so much the worse it will be for you, as they have done at Calicut and at Malacca.”

Historians have put forward the notion that if Rajah Humabon had not allowed Lapu-lapu to settle in the island of Cebu advising him instead to look elsewhere for land to settle further up north in the archipelago the course of Philippine history would be drastically different today.

Historians have put forward the notion that if Rajah Humabon had not allowed Lapu-lapu to settle in the island of Cebu advising him instead to look elsewhere for land to settle further up north in the archipelago the course of Philippine history would be drastically different today.

Soon after, as the merchant had warned, Span-ish conquistadores arrive on Visayan shores af-ter an arduous voyage of exploration through the Pacific Ocean. While the Aginid retells the story of how Humabon befriends the travelers, converts to Christianity and, according to Italian historian Antonio Pigafetta, requests Magellan to kill Lapu-lapu, the Aginid also relates how Lapu-lapu outplays, outlasts, outwits and eventually slays Magellan in the bat-tle of Mactan in the month of April 1521.

Out of the five ships and more than 300 men who left on the Magellan Expedition in 1519, only one ship (the Victoria) and 18 men returned to Seville in September 1522. Juan Sebastian de Elcano, the master of one of those ships, the “Concepcion” (which sank on the return trip), took over command. They started off through the westward route and re-turning to Spain by going east; Magellan and Elcano’s entire voyage took almost three years to complete but earned the distinction of being the first to circumnavigate the world in one full journey. It proved that the world was indeed round.

After that event, the Spaniards over the next 51-years came back to the Philippines in ships of expedition. The most notable one was commanded by Spanish-Basque explorer Miguel López de Legazpi and soon establish themselves as the colonial masters of the archipelago for the next 333-years (1565-1898).

This site is a member of the Filipi nos in New Zealand network of websites which can be accessed through its

This site is a member of the Filipi nos in New Zealand network of websites which can be accessed through its

It’s really fascinating if we can again use baybayin in writing for communication just like the japanese, chinese, russian, greek and korean characters that make the above-mentioned countries be identified because of their own alphabets.

Well, if Magellan had not arrived our history would drastically be different, too. Same would be if Humabon wasn’t a coward and lameduck to the Spaniards.

thumbs up….its good to know na marami pang tulad natin na interesadong alamin ang ating nakaraan , sabi nga ni Rizal “TO FORETELL THE DESTINY OF A NATION, IT IS NECESSARY TO OPEN THE BOOK THAT TELLS OF HER PAST

( Para malaman ang tadhana nang ating Bansa, kinakailangan upang buksan natin ang LIBRO na nagsasabi nang ating nakaraan)”

You are good. Write more …